- Sep 6, 2005

- 144,869

- 94,752

- AFL Club

- Fremantle

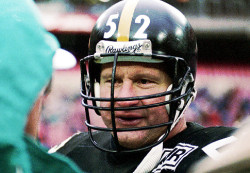

Re: NFL Concussions & Helmets

60 More Former Players Sue Over Concussions

60 More Former Players Sue Over Concussions

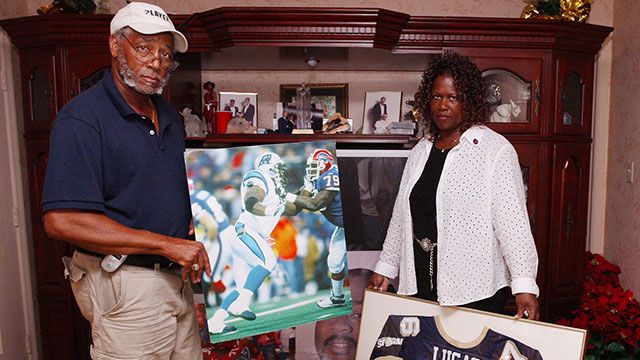

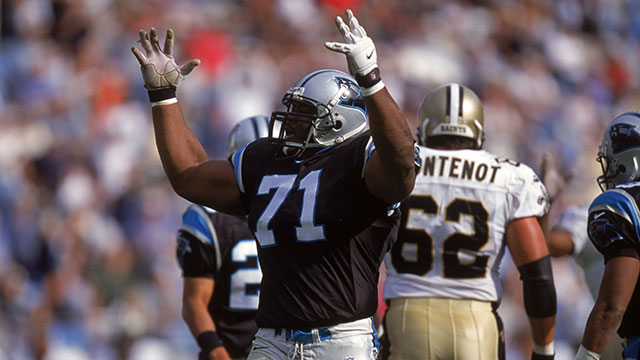

On Friday, via two separate legal actions, another 60 former players joined the growing list of men who are suing the NFL for the chronic consequences of concussions suffered while playing the game.

In Philadelphia, 49 players were added to a pending federal action that reflects the consolidation of numerous other suits. The latest 49 plaintiffs, including former 49ers quarterback John Brodie, are represented by the Locks Law Firm, which now represents 305 former players.

According to a press release forwarded to PFT, the players seek “medical monitoring, compensation, and financial recovery for the short-term, long-term, and chronic injuries, financial and intangible losses,” and other damages. Locks Law Firm says that additional suits will be filed in the coming weeks.

Meanwhile, a new suit was filed in New Orleans on behalf of 11 players, including former quarterback John Fourcade. “Wanting their players on the field instead of training tables, and in an attempt to protect a multibillion dollar business, the NFL has purposefully attempted to obfuscate the issue and has repeatedly refuted the connection between concussions and brain injury to the disgust of Congress, which has blasted the NFL’s handling of the issue on multiple occasions,” the new lawsuit contends, according to the Associated Press.

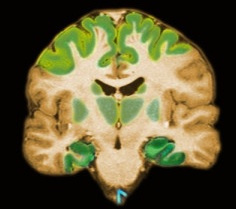

While the NFL apparently went through a period of denial regarding the link between concussions and chronic cognitive impairments, the challenge for the plaintiffs will be to identify the moment at which the NFL knew or should have known about the connection and the moment at which the NFL acknowledged the link and acted accordingly.

As a result, there necessarily will be some players who played before the NFL knew or should have known about the danger, and some who played after the NFL woke up to the problem.