Snake_Baker

The one true King of the North

- Apr 24, 2013

- 81,024

- 153,169

- AFL Club

- North Melbourne

- Other Teams

- Essendon Lawn Bowls Club

- Banned

- #1

GTFoutta here

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

LIVE: St Kilda v Western Bulldogs - 7:30PM Thu

Squiggle tips Saints at 51% chance -- What's your tip? -- Team line-ups »

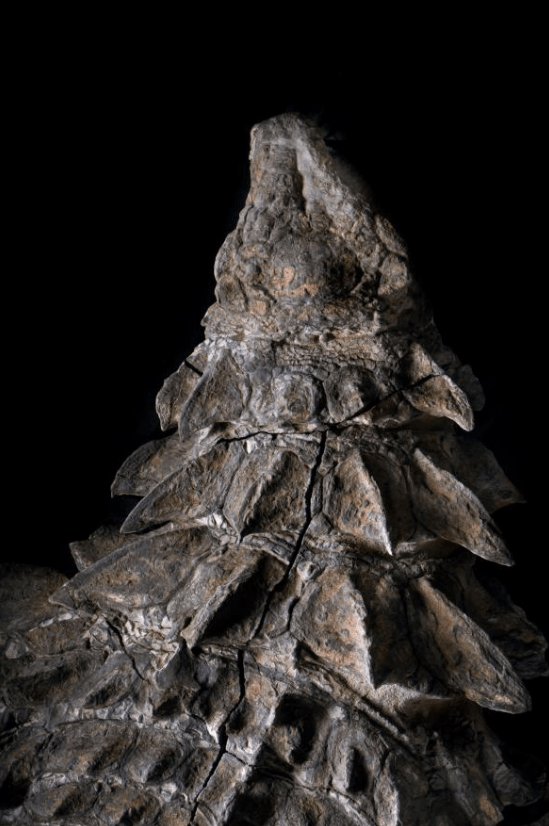

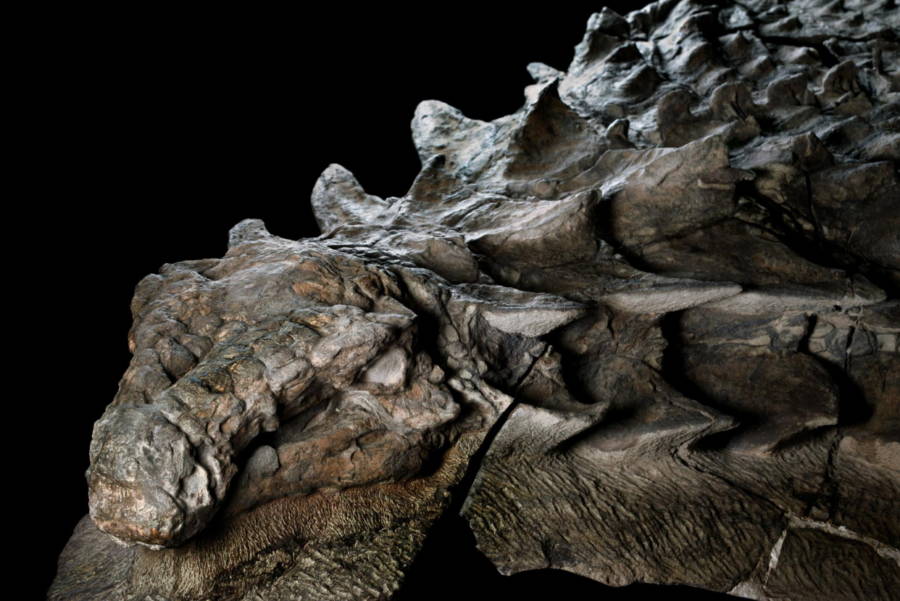

www.archaeology-world.com

www.archaeology-world.com