aussiedude

Pac-12 After Dark 2014-2023

- Feb 7, 2010

- 40,414

- 36,243

- AFL Club

- Collingwood

- Other Teams

- Green Bay Packers, Stanford

- Moderator

- #226

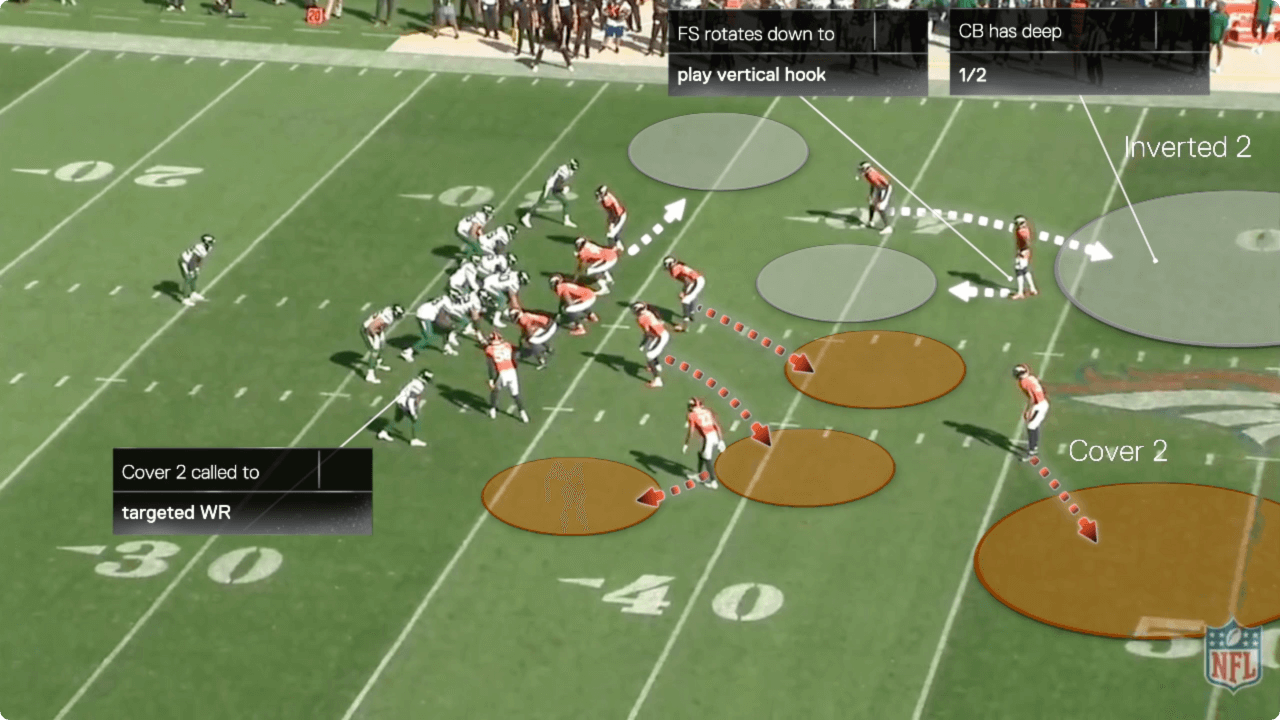

Madden has had access to it for a few years. but havent done much with it. Thats prob because not worth putting it into the card game that makes them all the money.