exe ex machina

Kylo was here

- Joined

- Sep 6, 2005

- Posts

- 152,728

- Reaction score

- 103,699

- Location

- San Marino

- AFL Club

- Tasmania

- Other Teams

- Dan Marino

Nice wikipedia page that highlights famous games and moments of every decade.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Football_League_lore

-----------

Games and plays

The following is a selected list of memorable plays and events that have stood the test of time and are considered common knowledge by NFL fans:

1920s

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Football_League_lore

-----------

Games and plays

The following is a selected list of memorable plays and events that have stood the test of time and are considered common knowledge by NFL fans:

1920s

- The Staley Swindle (December 4, 1921, Buffalo All-Americans vs. Chicago Staleys) The Staleys, having won every game of their 1921 season (partially by refusing to play any road games) except their Thanksgiving game against the then-undefeated All-Americans (who, other than their match against Chicago, also had played all of their games at home), challenged the All-Americans to a rematch. Buffalo, having already scheduled their last game for December 3, agreed on the condition that it be considered a "post-season" exhibition match and not be counted in the standings. When Chicago won the rematch 10-7, Staleys owner George Halas persuaded the league to count the game in the standings by playing two more games, in an effort to discredit the All-Americans' "post-season" claim and to bring their win percentage to the same as the All-Americans. The league then instituted the first-ever tiebreaker for the championship (a now discontinued rule stating that a rematch counts more than a first matchup) and handing the championship to Chicago. The "Staley Swindle" name is primarily used by Buffalo sports fans. The league was forced to place a finite end to the season after the incident; by 1924, when Chicago attempted to do the same thing with a post-season match against the Cleveland Bulldogs, the league disallowed it and allowed Cleveland to keep its title.

- 1925 Chicago Cardinals – Milwaukee Badgers scandal (December 10, 1925, Milwaukee Badgers vs. Chicago Cardinals) In 1925, the Chicago Cardinals were in the running to win the NFL championship with the Pottsville Maroons. The Maroons had beaten the Cardinals 21-7 earlier in the season at Comiskey Park. This loss gave Pottsville a half game lead in the standings. However, the Cardinals felt that they could make up for the loss. Many professional football teams during the first decade of the NFL would schedule some easy extra games to pad their record and place in the standing. The Cardinals had hoped that the move would help bump the team to a first place finish over Pottsville. Prior to 1933, the team with the best record in the standings at the end of the season was named the season's NFL Champions.The two extra games were scheduled against the Milwaukee Badgers and Hammond Pros, both of which were NFL members but had disbanded for the year. The Badgers had difficulty in fielding a team, so Art Folz, Chicago's substitute quarterback hired a group of high school football players to play for the Milwaukee Badgers, against the Cardinals. This would ensure an inferior opponent for Chicago. Upon his discovery NFL Commissioner, Joseph Carr, fined Chicago owner Chris O'Brien fined $1,000 for allowing his team play a game against high schoolers, even though he claimed that he was unaware of the players' status. Milwaukee owner Ambrose McGuirk was ordered to sell his Milwaukee franchise within 90 days. Meanwhile Art Folz, for his role, was barred from football for life. O'Brien's fine and Folz lifetime bann were recinded months later. However McGuirk already sold his franchise to Johnny Bryan.

- 1925 Pottsville Maroons The Pottsville Maroons were declared NFL champions after they defeated the Chicago Cardinals in a game that was moved to Chicago because the stadium in Pottsville was too small and the game had league championship implications. The Maroons won, 21-7. The next week they went on to play the University of Notre Dame All-Stars in a contractually obligated game, which included the Four Horsemen. That game took place in Philadelphia, at Shibe Park. The Maroons won that game in the last minute with a field goal, 9-7, stunned the crowd and legitimized professional football at a time when college football was considered superior. The NFL stripped the Maroons of their championship for supposed league violations and suspended the franchise for the remainder of the season. They were reinstated for the next season, out of fear they would defect to a newly created rival, the AFL. The controversy remains vivid to this day. The Chicago Cardinals' owner at the time, Chris O'Brien, refused the championship, calling it "bogus". The 1925 title was not claimed until Charles Bidwell purchased the team in 1932. Some people ascribe the Cardinals' ongoing futility to a "curse" from the people of Schuylkill County.

- December 18, 1932, Portsmouth Spartans vs. Chicago Bears, 1932 NFL Playoff Game[1] The first NFL Playoff game was the result of a tie in the standings between the 6-1-4 Portsmouth Spartans and the 6-1-6 Chicago Bears. At that time, ties were not counted in the standings, and both teams had played (and tied) each other twice. To solve the problem, the league decided to arrange a playoff game, the first in NFL history, to determine the league champion. The game was to be played at Wrigley Field, but due to severe blizzards and sub-zero wind chill, the game was moved indoors to Chicago Stadium, then used for hockey. Because of the size of the arena, several special rules were adapted for the game, including an 80-yard long field and goalposts on the goal line. The Bears ended up beating the Spartans 9-0. The popularity of the game led to the NFL splitting into two divisions, with the winners of each division playing in the NFL Championship game.

- "The Sneakers Game" (December 9, 1934, Chicago Bears vs. New York Giants, NFL Championship game)[1] The game was played at the Polo Grounds in frigid weather on a frozen field. At halftime, New York coach Steve Owen provided his team with basketball shoes for better traction. Gliding on the ice with the sneakers, the Giants scored 27 points in 10 minutes during the fourth quarter, and ended up beating the until-then undefeated Bears 30-13, winning the championship and denying the Bears their third straight championship (their second against the Giants) and the first undefeated and untied season in NFL history.

- December 8, 1940, Chicago Bears vs. Washington Redskins, 1940 NFL Championship Game Sparked by a comment made by Redskins owner George Preston Marshall, who had said three weeks earlier that the Bears were crybabies and quitters when the going got tough, Chicago crushed Washington, 73-0. This game currently stands as the most onesided victory in NFL history. Redskins quarterback Sammy Baugh was interviewed after the game, and a sportswriter asked him whether the game would have been different had wide receiver Charlie Malone not dropped a tying TD pass in the first quarter. Baugh reportedly quipped, "Sure. The final score would have been 73-7."

- December 16, 1945, Washington Redskins vs. Cleveland Rams, 1945 NFL Championship Game The Rams scored a safety when Redskins quarterback Sammy Baugh, throwing the ball from his own end zone, hit the goal posts (which were on the goal line between 1933 and 1973). The two points was the margin of victory as the Rams won 15-14. After the game, the rules were changed so that when a forward pass thrown from one's own end zone hits the goal posts, it is instead ruled incomplete. This rule is essentially null and void now that the goalposts are in the back of the end zone.

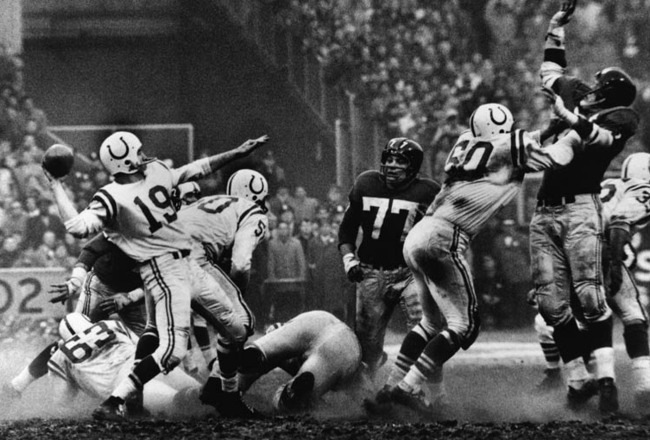

- "The Greatest Game Ever Played" (December 28, 1958, Baltimore Colts vs. New York Giants, NFL Championship game)[2] In the first-ever sudden death overtime in NFL history, Fullback Alan Ameche's 1-yard touchdown run gives the Colts a 23-17 win over the Giants. 17 future members of the Pro Football Hall of Fame were involved in the game. The nationally-televised game was watched by over 50 million people on NBC and helped springboard the NFL's popularity into the 1960s.

- The Wrong Way Run (October 25, 1964, Minnesota Vikings vs. San Francisco 49ers)[3] Vikings defensive end Jim Marshall picked up a fumble and accidentally ran 66 yards the wrong way, scoring a safety for the 49ers before he realized his mistake. Fortunately for Marshall, the Vikings prevailed, 27-22 due in part to a fumble Marshall caused later.

- The Hit Heard Round the World (1964 American Football League Championship Game, December 26, 1964, Buffalo Bills vs. San Diego Chargers) In the first of two consecutive league championships for the Buffalo Bills, Bills linebacker Mike Stratton laid a particularly bruising hit upon Chargers wide receiver Keith Lincoln that broke Lincoln's ribs and knocked him out of the game. It is considered one of the hardest hits ever leveled in a professional football game.[4]

- The Ice Bowl (December 31, 1967, Dallas Cowboys vs. Green Bay Packers, NFL Championship game) At Lambeau Field, the temperature was reported at -13 degrees Fahrenheit (-25 °C). The NFL Films presentation of this event, in which the playing surface was referred to as "the frozen tundra of Lambeau Field," has been the source of endless imitation and parody. The Packers won 21-17 on a Bart Starr Quarterback sneak with 16 seconds left, their third straight NFL title under coach Vince Lombardi.

- The Heidi Game (November 17, 1968, New York Jets vs. Oakland Raiders) With its nationally-televised game running late, NBC began to show the movie Heidi just moments after the Jets' Jim Turner kicked what appeared to be the game-winning field goal with 1:05 remaining. While millions of irate fans, missing the finale, jammed NBC's phone lines, the Raiders scored two touchdowns in eight seconds during the final minute to win 43-32.

- The Guarantee (January 12, 1969, AFL New York Jets vs. NFL Baltimore Colts, Super Bowl III)[5] The 19-point favorite Colts lose 16-7 to the New York Jets. Jets quarterback Joe Namath "guaranteed" a win for the Jets at The Miami Touchdown Club just a few days before the game.[6] After the Packers won the first two Super Bowls, the doubts about the AFL's ability to compete with the NFL had increased. This victory by the Jets helped quell those doubts, helping cement the NFL-AFL merger.

- The Immaculate Reception (also referred to as the Immaculate Deception by Raiders fans) (December 23, 1972, Oakland Raiders vs. Pittsburgh Steelers, AFC Divisional Playoff Game)[7] With Pittsburgh trailing Oakland 7-6 and facing fourth-and-ten on their own 40-yard line with 22 seconds remaining in the game, Steelers quarterback Terry Bradshaw threw the ball toward halfback John "Frenchy" Fuqua. However, the ball bounced into the air as Fuqua collided with Raiders safety Jack Tatum. It was then caught by Steelers fullback Franco Harris, who then ran the rest of the way downfield to score a touchdown that gave the Steelers a 12-7 lead with five seconds remaining in the game. The catch is controversial because it could not be determined by available camera angles whether the ball had been touched last by Fuqua, Tatum, or both. The NFL rules at the time dictated that two offensive players could not consecutively touch a forward pass unless and until an opposing player had touched it in between their touches. Therefore, if Fuqua touched the ball before Harris without Tatum touching it in the interim, the play should have been ruled dead as an incomplete pass. Under current rules, the play would be deemed legal.

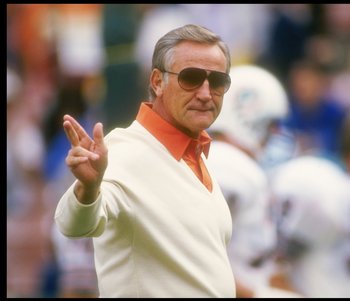

- Miami's Perfect Season (1972) The Miami Dolphins became the only NFL team to have a perfect season, capped by winning Super Bowl VII. It is a well-travelled urban legend that each year the surviving members of the team had made a ritual of getting together and drinking champagne when the last unbeaten team loses. In actuality, only a small group of ex-players - namely Bob Griese, Nick Buoniconti and Dick Anderson, who all live in Coral Gables, Florida - gathered to uncork the champagne and have a celebratory drink.[8]

- Garo's Gaffe (January 14, 1973, Miami Dolphins vs. Washington Redskins, Super Bowl VII) The Perfect Season almost ended with the first shutout in Super Bowl championship history, but with 2:07 to go in the game, Dolphins placekicker Garo Yepremian's 42-yard field goal attempt was blocked. Instead of falling on the ball, he attempted a forward pass, but let go of the ball before any forward motion because his hands were too small. The ball was fumbled, and returned by Redskins cornerback Mike Bass for a touchdown, cutting the Dolphins' lead to 14-7. To this day, no team has been shut out in a Super Bowl.

- The Sea of Hands (December 21, 1974, Miami Dolphins vs. Oakland Raiders, AFC Divisional Playoff Game) With 24 seconds left in the game, Raiders RB Clarence Davis somehow caught the game-winning touchdown pass among "the sea of hands" of three Dolphins defenders. This game eliminated Miami from the playoffs after they had made it to the Super Bowl in each of the last 3 seasons. Also known as the "Lost Game" due to both NBC and NFL Films losing their English copies of the broadcast. It was thought until recently that the only remaining copy was NBC's Spanish version, when NFL Films found their copy buried deep in storage, which they thought was lost in a move in the early 80's. [9]

- The Hail Mary (December 28, 1975, Dallas Cowboys vs. Minnesota Vikings, NFC Divisional Playoff Game)[10] The term Hail Mary pass first came to national awareness with this game. With 24 seconds left in the game, Cowboys quarterback Roger Staubach, nicknamed "Captain Comeback", threw a desperate 50-yard winning touchdown pass to "Mr. Clutch" Drew Pearson to defeat the Minnesota Vikings. Until this time, a last-second desperation pass had been called several names, most notably the "Big Ben."

- Ghost to the Post (December 24, 1977, Oakland Raiders vs. Baltimore Colts, AFC Divisional Playoff Game) Raiders tight end Dave Casper, nicknamed "The Ghost" by his teammates, caught a 42-yard reception (on a pass route headed towards the goal posts) to set up the Raiders' tying field goal near the end of regulation. Then Casper caught a 10-yard touchdown pass with 43 seconds into the second overtime period to win the game.

- The Holy Roller (September 10, 1978, Oakland Raiders vs. San Diego Chargers) The Raiders were trailing the Chargers with 10 seconds remaining. Quarterback Ken Stabler fumbled the ball and running back Pete Banaszak swatted it into the end zone where tight end Dave Casper fell on it for a touchdown. After this play, it was made illegal to move the ball forward by deliberately swatting or kicking it after a fumble; and in the final two minutes of each half, plus on fourth down at any time in the game, a forward fumble recovered by any member of the offensive team other than the fumbler is spotted at the point of the fumble, not the point of the recovery.

- The Miracle at the Meadowlands (also referred to as The Fumble by Giants fans) (November 19, 1978, Philadelphia Eagles vs. New York Giants) Leading 17-12 with 31 seconds left in the game (and the Eagles having no timeouts left), Giants quarterback Joe Pisarcik tried to hand off to running back Larry Csonka instead of simply kneeling with the ball to run out the clock. The exchange was fumbled and the Eagles' Herman Edwards picked up the loose ball and ran it in for the game-winning touchdown. The Eagles won 19-17 and the next day Giants' offensive coordinator Bob Gibson was fired, with head coach John McVay losing his job at the conclusion of the season. As a result of the botched late-game handoff, the so-called "victory formation" has become a standard across all levels of football at the end of games.

- Red Right 88 (January 4, 1981, Oakland Raiders vs. Cleveland Browns, AFC Divisional Playoff Game) Trailing 14-12, the Browns choose to attempt an end zone pass play (Red Right 88) instead of trying for a game-winning field goal in the final minute, but the pass was intercepted by Raiders safety Mike Davis. With that interception, the Raiders held on to eventually advance to and win Super Bowl XV. The air temperature was 4 degrees Fahrenheit, but wind chill was -36 °F.

- The Epic in Miami (also known as The Game No One Should Have Lost) (January 2, 1982, San Diego Chargers vs. Miami Dolphins, AFC Divisional Playoff Game) The temperature was 85°F (29.4°C) at the Miami Orange Bowl, but it did not stop either team's offense. This game set playoff records for the most points scored in a playoff game (79; the record has since been broken by the Packers and Cardinals in 2009), the most total yards by both teams (1,036), and most passing yards by both teams (809). By the end of the first quarter the Chargers stormed to a 24-0 lead, but the Dolphins cut their deficit to 24-17 by halftime and took a 38-31 lead on the first play of the fourth quarter. However, the Chargers went on to tie the game before time ran out, causing regulation to end with a 38-38 tie. In overtime, San Diego beat Miami, 41-38.

- Freezer Bowl (January 10, 1982, San Diego Chargers vs. Cincinnati Bengals, AFC Championship Game) One week after their victory over the Dolphins in "The Epic in Miami" in Florida's scorching heat, the Chargers travelled to Cincinnati to face the Bengals in the coldest game in NFL history based on the wind chill. The air temperature was -9 degrees Fahrenheit (-23 °C), but wind chill was -59 °F (-51 °C). In an attempt to intimidate the Chargers, several Bengals players went without long sleeved uniforms. Cincinnati won the game 27-7 and advanced to their first Super Bowl in franchise history.

- The Catch (January 10, 1982, Dallas Cowboys vs. San Francisco 49ers, NFC Championship Game)[11] With 58 seconds left and the 49ers down by 6, Joe Montana threw a very high pass into the endzone. Dwight Clark leapt and completed a fingertip catch for a touchdown. The 49ers won 28-27 and went on to win Super Bowl XVI.

- The Snow Plow Game (December 12, 1982, Miami Dolphins vs. New England Patriots) After a snowstorm held both teams scoreless, Patriots head coach Ron Meyer ordered the area where the ball was to be spotted for a field goal attempt cleared by a snow plow. Mark Henderson, a convict on work release, cleared the path for John Smith's attempt. It won the game for the Patriots, 3-0, and the practice of using snow plows during games was later banned.[12]

- Mud Bowl (January 23, 1983, AFC Championship Game, New York Jets vs. Miami Dolphins)[13] The game was played on a wet, muddy field which largely negated the Jets' advantage in speed at the skill positions, and emphasized the Dolphins' strengths; the Killer B's Defense and a solid power running attack. The Dolphins defense held Jets quarterback Richard Todd to only 15 of 37 completions for 103 yards and intercepted 5 of his passes. Linebacker A.J. Duhe led Miami with 3 interceptions, scoring a 35-yard touchdown and setting up the other Dolphins score in the 14-0 victory. Afterwards, the Jets complained about Dolphins coach Don Shula's decision not to place the tarp over the Miami Orange Bowl's grass field before the game. The Dolphins completed a 3 game sweep of the Jets with this victory, the first time this was accomplished in NFL history, and deepening the already bitter Dolphins–Jets rivalry.

- 70 Chip (January 30, 1983, Super Bowl XVII, Miami Dolphins vs. Washington Redskins) Trailing 17-13 in the fourth quarter, the Redskins were facing 4th and 1 in Miami territory. Washington running back John Riggins was the obvious choice to drive through the line for a first down. The play "70 Chip" was called in by offensive coordinator Joe Bugel. The play was designed for The Hogs to clear what appeared to be a path straight through the defensive line, but had a wing back, Clint Didier run across the formation, fake and come back to the left side and block the strong safety, opening up a hole on the left for John Riggins to run through. Riggins was usually known for straight ahead, line busting runs, taking several opponents to bring him down, not necessarily a long distance runner. While following Didier in motion, defensive back Don McNeal briefly slipped; although he recovered to try to stop the play, Riggins brushed him aside to run 43 yards for the touchdown and put the Redskins ahead 20 to 17. The run was immortalized by NFL Films showing Riggins' strength and determination all the way to the end zone, including the sound of a diesel train (Riggins' nickname). The Redskins went on to defeat the Dolphins 27-17, winning their first Super Bowl title. Riggins won the Super Bowl MVP Award for his efforts in the process.

- The Drive (January 11, 1987, Denver Broncos vs. Cleveland Browns, AFC Championship Game) After a muffed kickoff return, and trailing 20-13, the Broncos were positioned at their own two-yard line with 5:32 remaining in the game. In 15 plays, Denver quarterback John Elway drove his team 98 yards for a touchdown to tie the game, which the Broncos won in overtime to advance to Super Bowl XXI.

- The Fumble (January 17, 1988, Cleveland Browns vs. Denver Broncos, AFC Championship Game) Trailing 38-31 with 1:12 remaining in the game, the Browns' Earnest Byner appeared to be on his way to score the game tying touchdown, but he fumbled the ball at the 3-yard line. The Broncos recovered the ball, gave the Browns an intentional safety, and went on to win 38-33, sending the Broncos to their second consecutive Super Bowl appearance (Super Bowl XXII).

- The Fog Bowl (December 31, 1988, Philadelphia Eagles vs. Chicago Bears, NFC Divisional Playoff Game) A heavy, dense fog rolled over the stadium (Soldier Field) during the second quarter, cutting visibility to about 15-20 yards for the rest of the game. The fog was so thick that TV and radio announcers had trouble seeing what was happening on the field. The Bears ended up winning 20-12.

- The Instant Replay Game (November 5, 1989, Chicago Bears vs Green Bay Packers)[14][15] Late in the game, Green Bay quarterback Don "Magic" Majkowski rifled a desperation fourth-down pass into the end zone, caught by receiver Sterling Sharpe for a TD that would give the Packers a 14-13 victory with the extra point. However, a penalty flag was thrown, and it charged that Majkowski had thrown an illegal pass after he stepped over the line of scrimmage. After review, replay official Bill Parkinson ultimately ruled a touchdown for Green Bay. The Bears organization protested, and to this day, it is marked in their media guide as "The Instant Replay Game."

- Bounty Bowl (November 23, 1989, Philadelphia Eagles vs. Dallas Cowboys) In the Cowboys' annual Thanksgiving game, the Eagles won 27-0, in the only Thanksgiving shutout Dallas has suffered to date. The game was ill-tempered, with several scuffles between opposing players, and Cowboys (and former Eagles) kicker Luis Zendejas was knocked out of the game with a concussion thanks to a hard hit during a kickoff. After the game, Cowboys coach Jimmy Johnson accused Eagles coach Buddy Ryan of placing bounties on Zendejas and Dallas quarterback Troy Aikman.

- Bounty Bowl II (December 10, 1989, Dallas Cowboys vs. Philadelphia Eagles) The equally ill-tempered rematch, won 20-10 by the Eagles, was played in a Veterans Stadium that was not cleaned of snow that had fallen for several days in Philadelphia. The notoriously rowdy Eagles crowd, lubricated by considerable amounts of beer, threw snowballs, iceballs, batteries, and other objects at anyone in sight. One game official was knocked to the ground by a barrage of snowballs, Johnson had to be escorted from the field by Philadelphia police through a hail of debris, and CBS broadcasters Verne Lundquist and Terry Bradshaw had to dodge snowballs aimed at the broadcast booth. Even Eagles star Jerome Brown became a target when he stood on the players' bench pleading with fans to stop throwing debris on the field.

- The Body Bag Game (November 12, 1990, Washington Redskins vs. Philadelphia Eagles, Monday Night Football[16]) In the days leading to the clash, Eagles head coach Buddy Ryan threatened a beating so severe that "they'll have to be carted off in body bags." Ryan's words were prophetic. The Eagles defense scored three touchdowns in a 28–14 win and knocked eight Redskins out of the game, including two quarterbacks. The Redskins finished with running back-returner Brian Mitchell playing quarterback. Two months later, however, the Redskins would have the last laugh, returning to Philadelphia for a playoff game and defeating the Eagles 20-6.

- Wide Right (January 27, 1991, Buffalo Bills vs. New York Giants, Super Bowl XXV) With eight seconds remaining, Scott Norwood was called in to kick a 47-yard field goal for the Bills, who were down 20–19 against the Giants. The kick had plenty of distance, but sailed wide right, beginning the Bills' streak of four consecutive Super Bowl losses.

- The Comeback (January 3, 1993, Houston Oilers vs. Buffalo Bills, AFC Wild Card Playoff Game) With quarterback Jim Kelly, running back Thurman Thomas, and linebacker Cornelius Bennett out injured, Frank Reich led the Bills back from a 32-point deficit, to defeat the Oilers 41-38 in overtime in a wild card playoff game, thought by some to be the greatest comeback ever in pro football history. Incidentally, Frank Reich had quarterbacked the University of Maryland team to what was then the greatest comeback in college football history, during a 1984 game versus the University of Miami.

- The Clock Play aka The Fake Spike Game (November 27, 1994, Miami Dolphins vs. New York Jets) With 22 seconds remaining in regulation and trailing 24-21 in a battle for AFC East supremacy, the Dolphins had the ball at the Jets' 8-yard line but were out of timeouts. Running to the line of scrimmage, Dolphins quarterback Dan Marino yelled "Clock! Clock!" and motioned that he was going to spike the ball to stop the clock and set up an attempt at a game-tying field goal. The Jets defense, anticipating a spike, lined up haphazardly. Marino took the snap, but instead of spiking the ball, dropped back to pass. The Jets had bought the ruse and were caught off-guard, enabling Marino to deliver the game-winning touchdown pass to a wide open Mark Ingram in the front corner of the end zone. The 28–24 victory moved the Dolphins to 8–4 en route to the division title, while the Jets dropped to 6–6 and went on to lose their final four games in a season that culminated with the firing of head coach Pete Carroll. The Jets would reach new lows in the following two seasons, winning a total of 4 games over that span.

- The Helicopter (January 25, 1998, Denver Broncos vs. Green Bay Packers, Super Bowl XXXII) Late in the third quarter, with the scored tied 17-17, Denver faced a third and six at the Packers' 12 yard line. Quarterback John Elway, unable to find a receiver, held onto the ball and sprinted through the Green Bay defense. At the 6 yard line, and with Packers strong safety LeRoy Butler bearing down on him, Elway dove into the air. Despite missing Elway head-on, Butler got enough to send him spinning in mid-air like the rotors of a helicopter. Elway landed at the 4, enough for a first down, and leaped back into the huddle. The Broncos would score two plays later, and go on to win the team's first championship, 31-24. Elway's selfless play is credited with inspiring his teammates to victory.

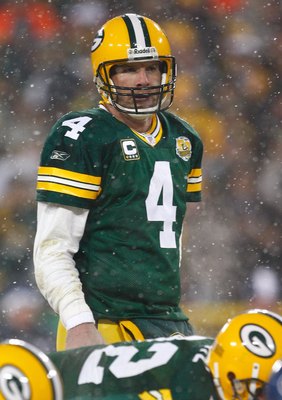

- The Catch II (January 3, 1999, Green Bay Packers vs. San Francisco 49ers, 1998 NFC Wild Card Playoff Game) Brett Favre, Mike Holmgren, and the Packers led 27–23 late in the game. However, the 49ers managed to get a late drive all the way down to Green Bay's 25-yard line. With 8 seconds left, QB Steve Young got the snap, stumbled for a bit, and then threw the game-winning TD pass to WR Terrell Owens. Owens (who until this point only had two receptions and many dropped passes) would get hit by two defenders, yet he would hold on to preserve the win. Many Packers fans contend that the drive never should have gotten that far down the field, as a Jerry Rice fumble was incorrectly ruled down by contact earlier on the drive.

- Music City Miracle (January 8, 2000, Buffalo Bills vs. Tennessee Titans, AFC Wild Card Playoff Game) With 16 seconds left in the game, the Titans received a kickoff. The Titans' Lorenzo Neal handed the ball to Frank Wycheck, who then lateraled the ball across the width of the field to his teammate, Kevin Dyson, who in turn ran the length of the field down the sideline for the game-winning touchdown (22-16). Controversy surrounded the play, hinging on whether Wycheck's pass to Dyson was an illegal forward pass, though the play was held up by instant replay review by referee Phil Luckett. The Tennessee Titans went on to lose the Super Bowl in the "One Yard Short" play.

- The Tackle/One Yard Short (January 30, 2000, St. Louis Rams vs. Tennessee Titans, Super Bowl XXXIV)[17][18] Trailing 23-16 with six seconds remaining in the game, the Titans, who had no timeouts left and possession of the ball on the Rams' 10-yard line, had one final chance to tie the game. Titans quarterback Steve McNair passed the ball to Kevin Dyson on a slant, but Rams linebacker Mike Jones came across the field and tackled Dyson perpendicular to the end zone. Dyson stretched out towards the goal line, but was only able to reach the one-yard line before being ruled down.

- The Monday Night Miracle (October 23, 2000, Miami Dolphins at New York Jets, Monday Night Football) Down by a score of 30-7 at the end of the third quarter, the New York Jets pulled together a rapid and improbable comeback with 4 touchdowns and 1 field goal in the fourth quarter, including a tackle-eligible play to John "Jumbo" Elliott, and won the game in overtime 40-37.

- Tuck rule game (January 19, 2002, Oakland Raiders vs. New England Patriots, AFC Divisional Playoff Game) This is also known as Snowjob for Raiders fans, and as the Snow Bowl for Patriots fans. With less than two minutes to play in regulation, the Patriots trailed the Raiders, 13-10, in a game played mostly under a driving snowstorm. Oakland defensive back Charles Woodson blitzed Patriots quarterback Tom Brady and sacked him, causing what appeared to be a fumble. The ball was recovered by the Raiders' Greg Biekert at the Oakland 42-yard-line. When referee Walt Coleman reviewed the play, he ruled it an incomplete pass because of the Tuck Rule (NFL Rule 3, Section 21, Article 2, Note 2) which states that "even if the player loses possession of the ball as he is attempting to tuck it back toward his body" it is still a forward pass. The Patriots retained possession, and later tied the game on a dramatic, 45 yard Adam Vinatieri field goal that barely cleared the crossbar with 27 seconds left in regulation — regarded as one of the greatest kicks of all time, given the conditions. They won the game in overtime on a 23-yard field goal. The rule had been addressed as correct after the season, and has not been altered.

- River City Relay (December 21, 2003, New Orleans Saints vs. Jacksonville Jaguars) With the Saints needing a victory to keep their postseason hopes alive, the Jaguars held a 20-13 lead with seven seconds left in regulation, and the Saints had possession on their own 25. In a scene evoking memories of one of the most famous college football plays of all-time, Aaron Brooks passed to Donté Stallworth for 42 yards, who then lateraled to Michael Lewis for 7 yards. Lewis lateraled to Deuce McAllister for 5 yards, and McAllister lateraled to Jerome Pathon for 21 yards and a touchdown. With the score 20-19, an extra point would have capped the miracle play and forced overtime. However, in an unlikely twist, John Carney, who in his career made 98.4% of extra points attempted and had not missed one in a full decade, inexplicably missed the extra point wide right, ending the game, and seemed to cause the Saints to miss the playoffs for yet another season. However, the Saints needed another team to lose that day, which they did not, rendering the missed extra point moot.

- January 10, 2004, Carolina Panthers vs. St. Louis Rams, NFC Divisional Playoff Game After Carolina jumped out to a 23-12 lead, St. Louis rallied back by scoring 11 points in the last 6 minutes to send the game into overtime. During the first possession of the first overtime period, the Panthers marched down to the Rams 22 yard line and kicker John Kasay made a 40-yard field goal that would have won the game, but the play was called back after a delay of game penalty. Kasay subsequently missed the 45-yard attempt wide right, and on the Rams ensuing possession, kicker Jeff Wilkins would attempt a 53-yard field goal. Unlike Kasay's, it was straight on, but it fell just inches short of the goalpost. On the first play of the second overtime period, and after Ricky Manning Jr. intercepted a Marc Bulger pass, Panthers QB Jake Delhomme threw a 69-yard touchdown pass to Steve Smith to give the Panthers the win in the fifth-longest game in NFL history, hand the Rams their first home loss in 14 games, and help pave the way for their appearance in Super Bowl XXXVIII.

- 4th and 26 (January 11, 2004, Green Bay Packers vs. Philadelphia Eagles) Down 17-14 with 1:12 on the clock and no time outs left in the NFC Divisional Playoff Game, the Eagles had 26 yards to go on fourth down. The play (74 Double Go) called for a 25-yard slant running route for wide receiver Freddie Mitchell, and saw Quarterback Donovan McNabb toss a perfect 28-yard strike to Mitchell deep into the Packers secondary. Packer safety Bhawoh Jue saw Mitchell running free and ran over to deliver a hit, but he was too late. Mitchell completed a leaping reception and was brought down at the Packers 46, giving the Eagles a first down. The play set up David Akers' 37-yard field goal attempt after McNabb ran for another first down. The field goal was good, and the game went into overtime, where Eagles star safety Brian Dawkins was able to intercept a Packers pass and return it 35 yards, setting up another Akers field goal try. The 31-yard kick was good, giving the Eagles a dramatic 20-17 victory in sudden death overtime. The play helped send the Eagles to their third straight NFC Championship Game.

- The Helmet Catch (February 3, 2008, New York Giants vs. New England Patriots, Super Bowl XLII) With the score 14-10 in favor of the New England Patriots, the Giants got the ball with just over 2 minutes to play. They were able to drive down the field with short plays but time was running down. Then, on a third-and-five, quarterback Eli Manning went into the shotgun and was soon surrounded by Patriot defenders. A couple of Patriots were able to grab Manning's jersey, but he broke free and scrambled away from the pile, setting his feet and firing the ball downfield to wide receiver David Tyree. Tyree leapt for the ball, tightly covered by Patriots safety Rodney Harrison, and completed the 32-yard reception by pinning the ball against his helmet, bringing the Giants to the 22 yard line with 58 seconds left. The Giants would soon score a touchdown with 35 seconds left, and held on to win the game.