Fulham are getting a damn good keeper for £8m.

Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

-

Mobile App Discontinued

Due to a number of factors, support for the current BigFooty mobile app has been discontinued. Your BigFooty login will no longer work on the Tapatalk or the BigFooty App - which is based on Tapatalk.

Apologies for any inconvenience. We will try to find a replacement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Up the Arse! Goons Thread

- Thread starter windyhill

- Start date

- Tagged users None

🥰 Love BigFooty? Join now for free.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

- Feb 13, 2018

- 1,814

- 1,412

- AFL Club

- Essendon

- Other Teams

- wombats

Nil all draw is on the cardsWe couldn't have asked for better pre season form, hopefully we don't lay an egg at Palace Saturday morning.

Uses we concede in injury time

Log in to remove this Banner Ad

Guys might need some tissues on stand by reading these

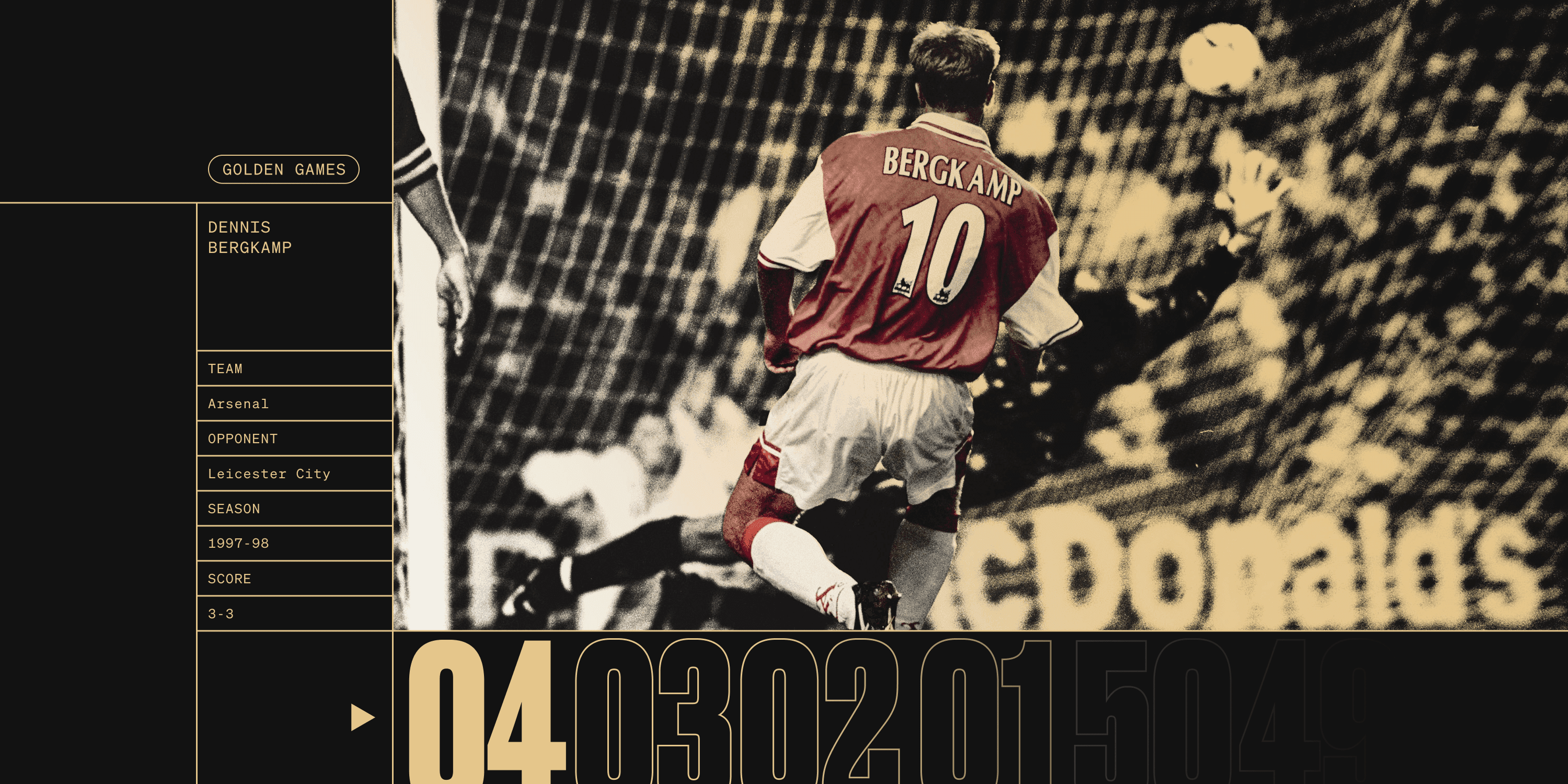

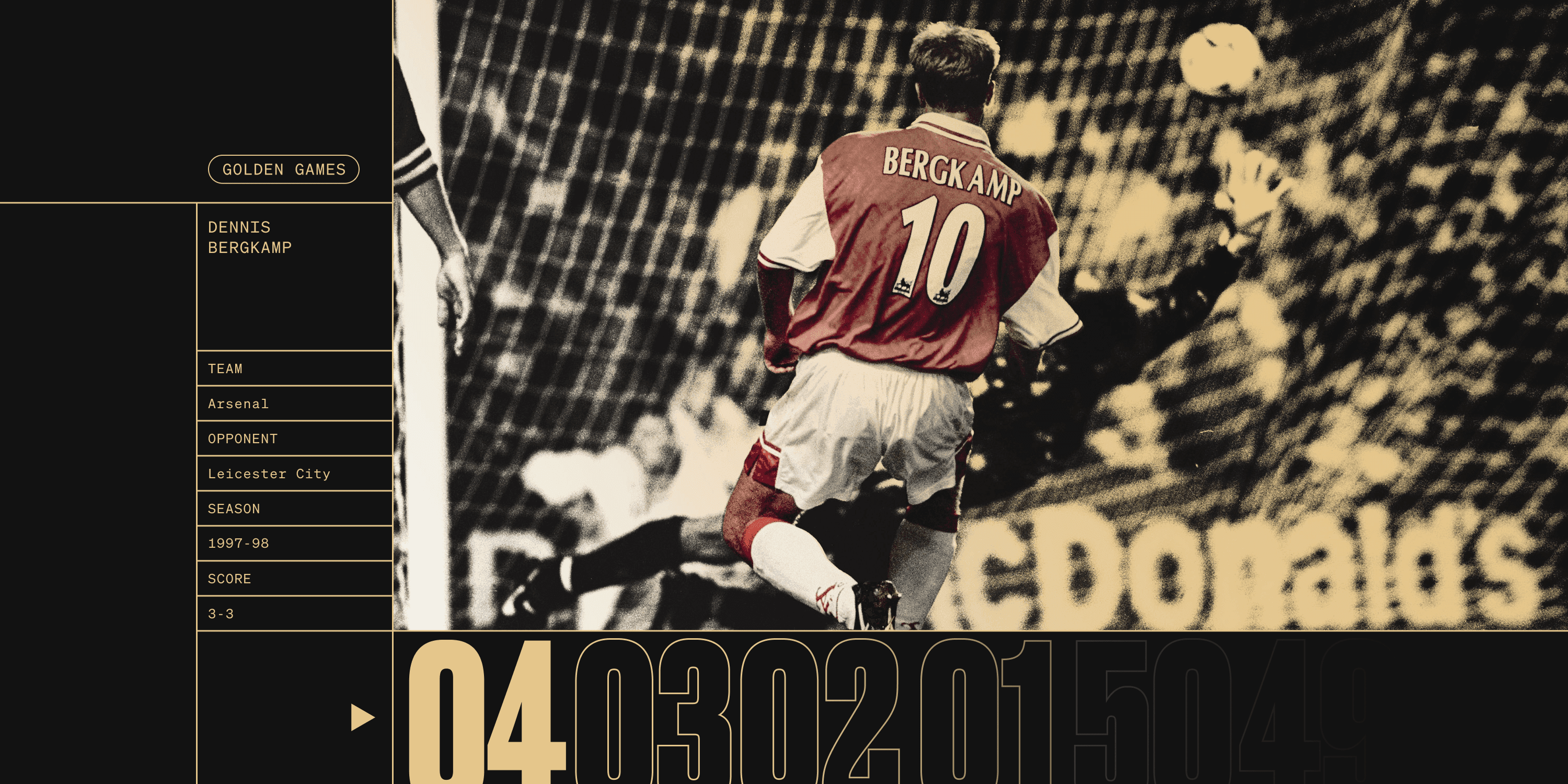

Emotions detonated like fireworks as the players of Leicester City and Arsenal made their way off the pitch and down the tunnel towards the dressing room. Steve Walsh, a hulk of a centre-half, and the livewire Ian Wright had been, in Wright’s words, “ding-donging” all game and they went for each other at the full-time whistle. Players from both substitutes’ benches rushed onto the pitch and into the melee. Even Arsene Wenger waded towards the action.

It was not entirely surprising everyone felt intoxicated by a cocktail of emotions. Arsenal dominated for large parts of the game but by the third minute of stoppage time, it had transmuted into some kind of wild footballing tornado. Three goals in four minutes, the upper hand lurching this way and that, embellished with one of the greatest virtuoso moments you could ever see. Emotional overload didn’t seem that unreasonable, really.

And in the middle of the maelstrom was Dennis Bergkamp. The Iceman. Dutch Master. This player of fiercely high footballing intellect was something else. He had just played 90 minutes that blew everyone away.

Once back in the visitors’ dressing room at Filbert Street, Bergkamp’s team-mates smothered him with accolades. “When you score a good goal the lads are all over you,” remembers Wright. “Everyone was hugging and congratulating him — we knew we had seen something miraculous. It is the kind of thing that makes you understand what you are now among. He is a world-class player. He scored two goals that were world class in that game.”

From the moment they met — by accident at a petrol station in a coincidence that had them both laughing — the rapport between Wright and Bergkamp was fascinating to observe, on and off the pitch. In so many ways, they seemed like opposites: Wright’s spontaneity and explosivity versus Bergkamp’s measured thoughtfulness. Wright’s extrovert personality versus Bergkamp’s natural reserve. They blended wonderfully. Even after all these years, Wright marvels at how his friend would do things in a way that felt so different to his own instincts.

A theme that runs through Bergkamp’s autobiography, Stillness and Speed, is the thought process behind each touch. It was something self-taught, something perfected over the hours and hours a young Bergkamp spent kicking a ball against the wall outside his Amsterdam home, constantly analysing how the ball moved a certain way depending on which part of the foot he used and what type of touch he tried, aiming for different corners of different bricks to work out the angles and geometry as the ball moved. He became evangelical about the first touch. Few boys would be as obsessed with breaking it all down in their youth, just for their own interest. But few are like Bergkamp.

“When you read his book he has the idea that there has to be a thought to every pass. I don’t think like that, but he is so intelligent it adds something,” Wright says. “When you are playing he is seeing the whole picture, but I am just seeing where I am and what I am doing.

“When you try to explain his speed of thought it is amazing. It is not instinctive. He is always messing around doing skills, rolling the ball, but when you see him do that beautiful bit of ballet at the point of highest pressure, that is what he is about. He knows how that works, how the body has to be, what the angles are. It was all beautiful in the movement. It has happened in his head already so he knows how to manipulate the ball. People say it is instinctive brilliance but not from Dennis. It is all thought. He knows the outcomes and sees the pictures and patterns and puts it into action.

“It’s there and you just have to unlock it. The closer you are to the box the more defenders have to try to stop you. He was making them move all the time to try to find space. All of a sudden, the magical bit is his action when the space has appeared. That is what he was working for.”

Look at Bergkamp’s first touch for the opening goal against Leicester. That is what sets him up. When Marc Overmars angles the ball towards his compatriot, positioned deep just outside the lower corner of the penalty area, Bergkamp opens his body and nudges the ball to enable him to curl his finish into an unstoppable pinpoint of the goal. He makes it look effortless, casual even. But the combination of knowing exactly what he would do, and the added quality of the touch, made it unpredictable and perfect.

“Dennis went out and put it straight into the stanchion,” says Wright. “Just like that. Before we know what’s going on we were 1-0 up out of nothing.”

The second was also about the first touch, to cleanly take the ball away in between two defenders and into the space between him and Leciester’s goalkeeper. The shot ricochets off Kasey Keller on its way in, which makes it look scruffier than his other goals, but at that moment he was in such flowing form even a master assister didn’t feel the need to take the safer option. “I was to his left and he might have knocked it back for me to tap in,” says Wright, “but it was his day.”

The hat-trick goal is a work of art. Again, the first touch is fundamental. As David Platt hooks a floating ball forwards, Bergkamp is sprinting onto it with the ball dropping over his shoulder. The way he kills the ball befuddles his marker, Matt Elliott.

“They don’t expect a player to be that good, and his touch to be that good, when the ball comes from that far,” says Wright. “That is when opponents underestimate the world-class players. The defender overcommitted himself. We had seen Dennis do things in training where his touch is so amazing, and we were used to that, but doing it in games is something else. Flick it, flick it, cushion it, place it. He could work out the goal, the components. Dennis was just doing his stuff. It was beautiful.”

Oh, what a match-winner it would have been… but Leicester had reserves of fighting spirit and an aerial bombardment from a late corner denied Bergkamp that extra satisfaction of his hat-trick delivering a victory. The fiery exchanges at the final whistle led to an FA charge and warning for Wright, Walsh and Patrick Vieira.

The rumpus was soon forgotten. Bergkamp’s hat-trick, an ode to the art of the touch, will live on.

Wright believes it should also be of use in the world of coaching — preferably at Arsenal.

“I’d love them to find a role for him,” he says. “To have a player with that technical ability, understanding and prowess, if he could pass any of that on to anybody, they are going to benefit from that. For Dennis to not be in some technical capacity seems like a massive waste. If there is something that can be done, Arsenal or anywhere, it has to be done to capitalise on the way his brain sees the game.”

Emotions detonated like fireworks as the players of Leicester City and Arsenal made their way off the pitch and down the tunnel towards the dressing room. Steve Walsh, a hulk of a centre-half, and the livewire Ian Wright had been, in Wright’s words, “ding-donging” all game and they went for each other at the full-time whistle. Players from both substitutes’ benches rushed onto the pitch and into the melee. Even Arsene Wenger waded towards the action.

It was not entirely surprising everyone felt intoxicated by a cocktail of emotions. Arsenal dominated for large parts of the game but by the third minute of stoppage time, it had transmuted into some kind of wild footballing tornado. Three goals in four minutes, the upper hand lurching this way and that, embellished with one of the greatest virtuoso moments you could ever see. Emotional overload didn’t seem that unreasonable, really.

And in the middle of the maelstrom was Dennis Bergkamp. The Iceman. Dutch Master. This player of fiercely high footballing intellect was something else. He had just played 90 minutes that blew everyone away.

Once back in the visitors’ dressing room at Filbert Street, Bergkamp’s team-mates smothered him with accolades. “When you score a good goal the lads are all over you,” remembers Wright. “Everyone was hugging and congratulating him — we knew we had seen something miraculous. It is the kind of thing that makes you understand what you are now among. He is a world-class player. He scored two goals that were world class in that game.”

From the moment they met — by accident at a petrol station in a coincidence that had them both laughing — the rapport between Wright and Bergkamp was fascinating to observe, on and off the pitch. In so many ways, they seemed like opposites: Wright’s spontaneity and explosivity versus Bergkamp’s measured thoughtfulness. Wright’s extrovert personality versus Bergkamp’s natural reserve. They blended wonderfully. Even after all these years, Wright marvels at how his friend would do things in a way that felt so different to his own instincts.

A theme that runs through Bergkamp’s autobiography, Stillness and Speed, is the thought process behind each touch. It was something self-taught, something perfected over the hours and hours a young Bergkamp spent kicking a ball against the wall outside his Amsterdam home, constantly analysing how the ball moved a certain way depending on which part of the foot he used and what type of touch he tried, aiming for different corners of different bricks to work out the angles and geometry as the ball moved. He became evangelical about the first touch. Few boys would be as obsessed with breaking it all down in their youth, just for their own interest. But few are like Bergkamp.

“When you read his book he has the idea that there has to be a thought to every pass. I don’t think like that, but he is so intelligent it adds something,” Wright says. “When you are playing he is seeing the whole picture, but I am just seeing where I am and what I am doing.

“When you try to explain his speed of thought it is amazing. It is not instinctive. He is always messing around doing skills, rolling the ball, but when you see him do that beautiful bit of ballet at the point of highest pressure, that is what he is about. He knows how that works, how the body has to be, what the angles are. It was all beautiful in the movement. It has happened in his head already so he knows how to manipulate the ball. People say it is instinctive brilliance but not from Dennis. It is all thought. He knows the outcomes and sees the pictures and patterns and puts it into action.

“It’s there and you just have to unlock it. The closer you are to the box the more defenders have to try to stop you. He was making them move all the time to try to find space. All of a sudden, the magical bit is his action when the space has appeared. That is what he was working for.”

Look at Bergkamp’s first touch for the opening goal against Leicester. That is what sets him up. When Marc Overmars angles the ball towards his compatriot, positioned deep just outside the lower corner of the penalty area, Bergkamp opens his body and nudges the ball to enable him to curl his finish into an unstoppable pinpoint of the goal. He makes it look effortless, casual even. But the combination of knowing exactly what he would do, and the added quality of the touch, made it unpredictable and perfect.

“Dennis went out and put it straight into the stanchion,” says Wright. “Just like that. Before we know what’s going on we were 1-0 up out of nothing.”

The second was also about the first touch, to cleanly take the ball away in between two defenders and into the space between him and Leciester’s goalkeeper. The shot ricochets off Kasey Keller on its way in, which makes it look scruffier than his other goals, but at that moment he was in such flowing form even a master assister didn’t feel the need to take the safer option. “I was to his left and he might have knocked it back for me to tap in,” says Wright, “but it was his day.”

The hat-trick goal is a work of art. Again, the first touch is fundamental. As David Platt hooks a floating ball forwards, Bergkamp is sprinting onto it with the ball dropping over his shoulder. The way he kills the ball befuddles his marker, Matt Elliott.

“They don’t expect a player to be that good, and his touch to be that good, when the ball comes from that far,” says Wright. “That is when opponents underestimate the world-class players. The defender overcommitted himself. We had seen Dennis do things in training where his touch is so amazing, and we were used to that, but doing it in games is something else. Flick it, flick it, cushion it, place it. He could work out the goal, the components. Dennis was just doing his stuff. It was beautiful.”

Oh, what a match-winner it would have been… but Leicester had reserves of fighting spirit and an aerial bombardment from a late corner denied Bergkamp that extra satisfaction of his hat-trick delivering a victory. The fiery exchanges at the final whistle led to an FA charge and warning for Wright, Walsh and Patrick Vieira.

The rumpus was soon forgotten. Bergkamp’s hat-trick, an ode to the art of the touch, will live on.

Wright believes it should also be of use in the world of coaching — preferably at Arsenal.

“I’d love them to find a role for him,” he says. “To have a player with that technical ability, understanding and prowess, if he could pass any of that on to anybody, they are going to benefit from that. For Dennis to not be in some technical capacity seems like a massive waste. If there is something that can be done, Arsenal or anywhere, it has to be done to capitalise on the way his brain sees the game.”

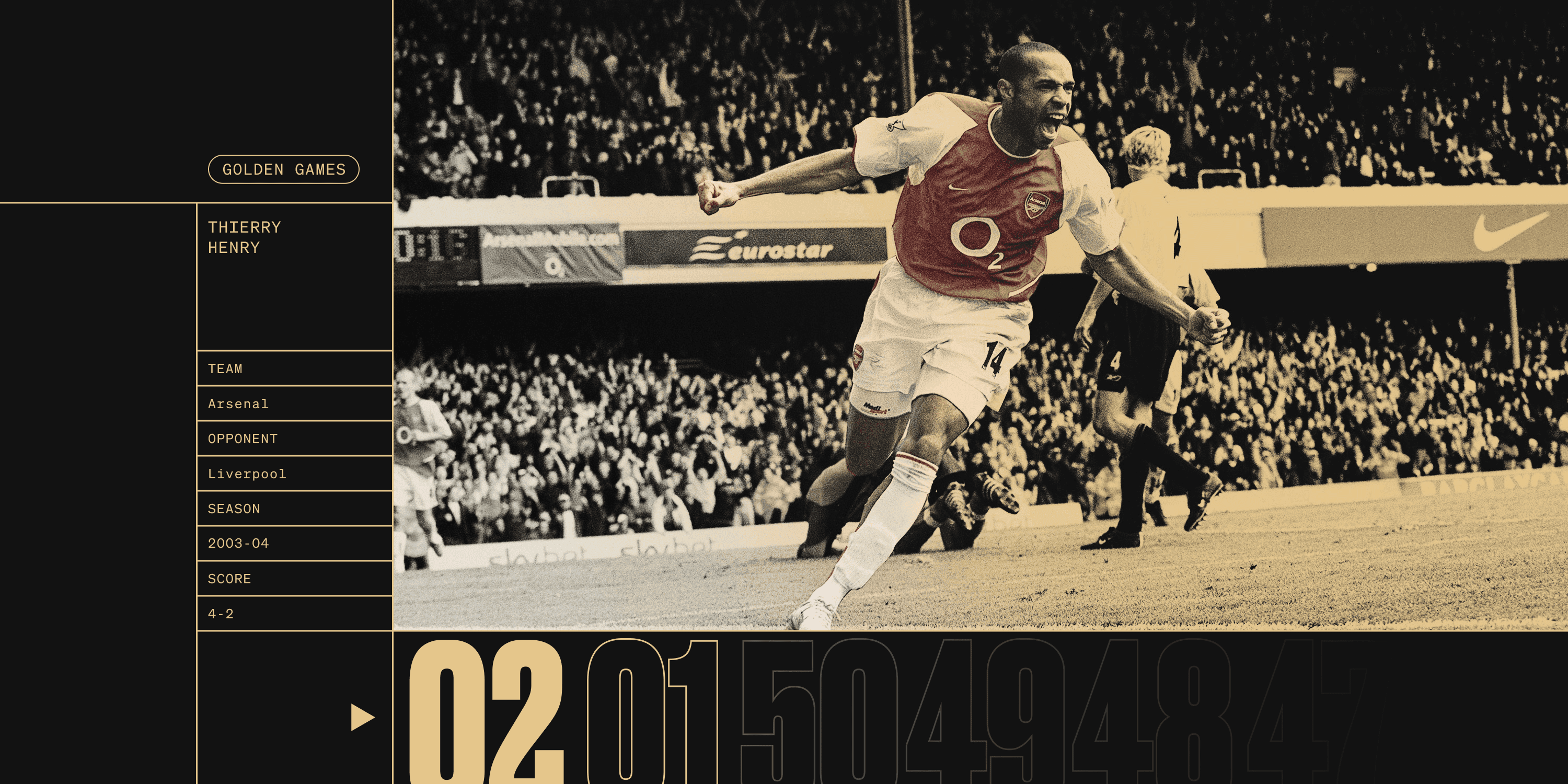

Remember the Highbury Screamer? She became known for panicked shrieks just as an opponent was about to shoot against Arsenal at Highbury. It must have been the ideal pitch for television microphones to pick up as her alarm call became a feature of broadcasts at the old stadium.

The sense of impending peril felt particularly ominous when the Highbury Screamer went full Edvard Munch on 9 April 2004. As Michael Owen pulled back his foot to guide Liverpool in front just before half-time, Arsenal’s entire universe was imploding.

It had been a hellish week. Seven days earlier, Arsenal had been in pursuit of a treble. But a series of stumbles left them in serious trouble. They lost the FA Cup semi-final against Manchester United, were painfully ejected from the Champions League by Chelsea, and trailed in the Premier League to Liverpool.

Their unbeaten run and confidence frayed to breaking point. The dressing room at half-time was thick with suffocating fear. “I felt that the stadium stopped breathing,” recalls Thierry Henry. “We were having such a great season, people were talking about the treble, and in a week we lost everything.”

Arsene Wenger was a student of the different types of motivation. “Intrinsic motivation comes from people who set themselves targets,” he once said. “They have an internal need to push themselves. They carry some sort of suffering inside, a dissatisfaction, that they transform into motivation. That motivation comes from the desire to always improve, to set themselves targets, and to analyse what they do.

“Then you have people with extrinsic motivation. They are motivated by goals coming from outside — people say to them, ‘You have to do this much in the game’, or, ‘If you do that, you will get the big bonus’. And they would do it.”

Looking around the dressing room at half-time, Wenger was acutely aware of the need for an injection of powerful motivation. Patrick Vieira described it as emotionally one of the hardest scenarios he had come across. Martin Keown, a substitute on the day, felt worried by the inertia that gripped and was desperate for his team-mates to pull themselves together, and he told them so.

They did, by summoning the style and spirit that generally served them so well, even though it required every ounce of resolve in the circumstances.

Back on the pitch, Henry drifted in from the left to jab a pass across. Freddie Ljungberg helped it on and Robert Pires arrived with typically intuitive timing to equalise. The relief was palpable, but anxiety still knocked around as nobody felt the result was yet safe.

Henry went into overdrive to banish all of Arsenal’s nervousness and revive the team completely. He had 10 opponents between him and the goal when he picked up the ball level with the centre circle. He revved himself up, bobbed and weaved at breakneck speed between them, and for the climax of his virtuoso run bent his strike past Jerzy Dudek. It was a goal of staggering audacity, tenacity and ability. Henry span off with his own alternative version of the Highbury Scream — this one was joyous, pumping with adrenaline, and presumably a couple of octaves lower. The Highbury crowd lost itself in pandemonium.

It was an extraordinary strike at an extraordinary moment for his team. Henry himself described it in the book Invincible as “more than a goal” — it was a trigger that enabled everyone to feel their hopes coming back to life. “It is the only time that I felt a stadium breathing again. I never had that feeling ever again. I have never seen a team feel such vibrations. We responded with our heart.”

Henry’s hat-trick goal, set up by Dennis Bergkamp, was scruffier, but important nonetheless as it took the game beyond Liverpool’s reach in both scoreline and psychology. Gerard Houllier described Henry as unplayable that second half. It was an individual performance that tilted everything for his team.

Not all players are comfortable with the extra pressure that comes with being a main protagonist. Even in a team as expert across the board as Arsenal’s that season, the rest of the players did have a tendency to trust that their main front men would deliver when needed. Henry and Bergkamp embodied that special quality to be a difference maker.

Vieira elaborated: “We were expecting someone to do something magical and it happened. We wanted for him to do it. He was there for us. When you are struggling you expect him, or Dennis, to do something.”

Let’s go back for a moment to Wenger’s point about intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Walking out the tunnel and into the second half against Liverpool, Henry felt pushed by both. The external factor was the aim to win the title and go unbeaten, with all the accolades that come with such an accomplishment. But the intrinsic motivation gives a fascinating insight into Henry the person, and how driven he was.

He pulled his inspiration from deep within, coaxed by a grudge of sorts, feeling wronged in a game against Liverpool that happened three years previously.

The 2001 FA Cup final planted a deep-seated and very personal sense of determination when it came to fixtures against Liverpool. Arsenal’s dominance that day was wrecked by two late Owen goals, but what really rankled was a pivotal decision early on. Stephane Henchoz handled a shot off the line to deny what would have been an Henry goal to give Arsenal a two-goal cushion. But there was no goal, no penalty and no red card for Henchoz.

“That game was a joke,” Henry reflected. “I was devastated. I came back home — how can you lose a game like this? It was so hard to take. I said to myself, especially when I used to play against Liverpool, I felt something special. I used to think about that FA Cup final and make sure that they were going to suffer, not us, again.”

So there you have it. Not only was Henry a rare footballer because of his wondrous cocktail of skills, daring and physical prowess, he was also unusual in terms of his very exacting sense of motivation and a desire to win fuelled by his own emotions.

It made him the vital player he was — one who could react, shoulder the expectancy on him, make the difference. Without those characteristics at that nadir against Liverpool, perhaps Arsenal’s Invincibles would never have been.

- Banned

- #9,958

Nervous about Saturday morning, absolute desperate need for get this season off to a good start, good starts are something we'll really lacked for a substantial amount of time.

So often we have these lethargic starts that leave you less margin for error over the course of the season.

Would be nice to simply just take 14 or 15 points from our 1st 6 games for a change.

Still want a CM and LW before the window closes at the end of the month.

So often we have these lethargic starts that leave you less margin for error over the course of the season.

Would be nice to simply just take 14 or 15 points from our 1st 6 games for a change.

Still want a CM and LW before the window closes at the end of the month.

*£3m.....

Bargain, surprised there weren’t more clubs interested, he’s not exactly shit

Mari and patino gone, Mari sold, patino out on loan, moving on players pretty fast atm

Bargain, surprised there weren’t more clubs interested, he’s not exactly s**t

Mari and patino gone, Mari sold, patino out on loan, moving on players pretty fast atm

Just the right set of circumstances for Fulham to acquire him so cheaply. One year left on his contract, large wages and difficult to shift, wants to stay in London, already been replaced at Arsenal etc etc. They’ve got an excellent deal there.

- Banned

- #9,964

Still sounds like we are interested in a player or 2...

Good, we need another 2 signings or we're left hoping Partey, Jesus and Saka are able to play 35 + league games.

- Aug 31, 2008

- 27,363

- 60,343

- AFL Club

- Hawthorn

- Other Teams

- Nuggets

Hopefully Torreira and Mari are moved on.

We need to sign a midfielder.

We need to sign a midfielder.

- Banned

- #9,966

Hopefully Torreira and Mari are moved on.

We need to sign a midfielder.

And another wide forward unless we really think Martinelli will go up 2 levels this season.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 2K

- Views

- 35K

- Replies

- 55

- Views

- 8K